Why we still need to talk about Unconscious Bias

The Human Analytics Project - 2020

WHAT WE THOUGHT WE KNEW...

Unconscious bias has become a recurring theme in the news of late. Despite extensive legislation and in-house training programmes, it remains a hot topic and rightly so. Gender-based pay inequalities continue to exist, there are still huge disparities in representation of racial and ethnic minority participants in most of our institutional settings, and medical outcomes still reveal differential treatment based on race, ethnicity and gender… the list goes on.

The starting point to tackling the problem of unconscious bias is to understand it. And it’s here we come up against our first obstacle. We thought we knew…

...WHAT UNCONSCIOUS BIAS IS

For example, prejudice and bias have often been represented as unitary concepts. When thinking about what bias is, we rightly make a clear distinction between explicit and implicit bias: the former as a consciously held belief or set of beliefs that result in purposeful discriminatory or aggressive behaviour; the latter as internalized beliefs that are not consciously espoused but play out in more subtle ways.

We did not, however, appreciate, how varied implicit (or ‘unconscious’) biases are and the ways they manifest in different forms of micro-aggressive behaviour. Examples of subtle expressions of bias are something we have all seen, whether a relatively passive, non-verbal behaviour of someone avoiding a handshake with a person from an ‘out-group’, to an unintentionally discriminatory non-verbal or verbal action that comes from an underlying stereotype. (see Box 1)

We may even have experienced this ourselves, such as when we are surprised by a biased thought popping into our own head, unbidden and unrepresentative of our personal ideology.

While we might expect the research literature to help our understanding of unconscious bias, it acts as a barrier. It is widely disparate, often inconclusive and always hotly contested for several reasons:

The notion of unconscious bias is paradoxical. If it is unconscious, how can we be sure what it is and how can we measure it? If we can’t measure it, how can we know its contribution to behaviour and how to change it?

Different academic paradigms. Social scientists describe the idea of unconscious bias in different ways, including latent, implicit, automatic and inaccessible. Such a wide range of terminology comes from the different lenses through which the subject is studied. Each set of academics (social psychologists, cognitive psychologists, sociologists, neuropsychologists and organisational psychologists) cling onto their preferred language and theoretical premise at the expense of common understanding.

Bias is emotional. Another problem is that bias is a very emotive subject, and this has led to emotionally-loaded rhetoric, abuse and lack of objectivity in much of the writing about it, including the academic literature. Partly, this is also a result of bias as a political issue very central to the diversity agenda.

Although the social science literature offers us no real consensus about a definition for unconscious bias, there is a good, in the sense of being both research-based and practical, approach to understanding the phenomenon. We’ll come to this once we finish looking at what we thought we knew.

WHAT WE THOUGHT WE KNEW...

...HOW TO MEASURE IT

Awareness of unconscious bias has risen hand in hand with use of the Implicit Association Test, or the IAT. Developed by a group of academics from Harvard and other US academic institutions, the test has become synonymous with unconscious bias training programmes where it is used to gauge an individual’s level of bias before moving on to strategies for managing and reducing it.

Each of the test versions available (race, gender, sexuality, weight and age) works by measuring the strength of association between concepts, such as ‘men versus women’ or ‘light skinned versus dark skinned’ and good and bad evaluative words such as ‘fantastic’ or ‘hurtful’. The theory is that reaction times are quicker when pairing learned associations.

Test respondents might, for instance, be quicker to pair ‘woman’ with ‘nurse’, and ‘man’ with ‘engineer’ rather than the other way around because they hold a bias (unconscious or not) that says women tend to be nurses and men tend to be engineers.

The test results are immediate and come with a disclaimer that they are not a definitive measure of implicit preferences and are given for educational purposes only. However, the results also include information on how implicit preferences are related to discrimination in hiring, promotion, medical treatment and decisions relating to criminal justice.

Our exploration of the academic literature and popular press shows the IAT has its critics, many of whom question whether it is a useful or meaningful measure at all.

Firstly, the IAT does not meet the recognised technical standards of a psychometric assessment measure, resulting in questions around its usefulness. For example, if you take the same test on two different occasions the results are often different. Your score may also be influenced by factors other than biases such as age, concentration levels and your processing speed.

Secondly, there is no clear evidence linking IAT scores to actual behaviour. If the IAT shows you have biases, there’s no certainty you are more likely to act out that bias in real life. It is true that many studies have reported associations between scores on the IAT and various measures of biased social evaluations, often in a laboratory setting, but this is not the same as saying the test predicts real-world behaviour. Without this evidence, the IAT cannot be justified as a tool for identifying who is more likely to be biased in real life.

Furthermore, the literature on bias often confuses stereotypes with prejudice. Some have argued that the IAT does not necessarily measure negative attitudes, but instead measures an internalising of commonly held stereotypes about people – attributes we have learned to associate with a certain group of people because of our experience. These social biases may be at odds with our consciously held beliefs, but they can and do play out in subtle ways.

All this then begs the question as to what use the test has.

The most sensible answer is that it does have some value as an awareness-raising tool, provided the appropriate caveats are made, and it is handled carefully and sensitively. This can be tricky. Some of the concepts and messaging are subtle and complex and it is all too easy to interpret the results as showing a respondent to be racist or sexist.

The issues with the IAT highlight the challenge of measuring something that is an unconscious process as well as the challenges of measuring how these unconscious processes translate into real-world behaviour.

The paradox that faces psychologists and diversity practitioners is that if you can’t measure something, how can you know it exists, let alone whether it has changed because of training and education?

At the moment though, the IAT and its close cousins, is the best measure we have.

WHAT WE THOUGHT WE KNEW...

… HOW TO CURE IT

We’ve come a long way…or have we?

In 2020, we still find ourselves in a situation where fewer African-American male job applicants with a positive employment history will be successful in their being hired than white males with criminal records.

The high profile of unconscious bias has resulted in many proposed and actual mitigation/remedial strategies. Some of these aim to counteract the effects of bias through bias mitigation while others attempt bias reduction.

The efficacy of different types of intervention has been the subject of much research.

Our investigation of the literature revealed the following:

Most interventions aim to mitigate the effects of bias through various ‘habit-breaking’ mechanisms. Typical methods range from self-directed book-based or online learning to forms of interactive workshop programmes.

The content of interventions use a variety of techniques including:

cognitive learning (knowledge acquisition around cultural diversity issues, theories around unconscious bias, the effects of bias and so on);

attitudinal learning (understanding and trying to change attitudes - if adverse - to diversity through changing trainees’ beliefs in their self-efficacy);

and behavioural learning (skills development, for example, the ability to perform an objective performance appraisal).

Most training includes a combination of elements of all three types of learning, although as noted above, most employ cognitive and behavioural learning to try and counteract, or mitigate, the effects of bias. It is typically presented as ‘awareness raising’ plus delivery of some mitigating cognitive and/or behavioural strategies.

However, there is little evidence to suggest that significant behaviour change is achieved. Where there is some reduction in unconscious bias - generally measured through expressed intentions rather than actual behaviour - it does not tend to sustain for prolonged periods (for example, longer than three months).

The most promising avenues for such interventions are cognitive learning strategies – mainly education/awareness raising, and there is a positive relationship between the length of the programme and the effectiveness of the programme in mitigating bias.

What seems to work best is: EDUCATION + STRATEGIES + PRACTICE.

WHY DOES INSIGHT FAIL US?

We thought we knew that awareness and self-knowledge would liberate us from unconscious bias. That with a little reflection we could all generate some insight into the layers of ancestral, cultural, generational, political, religious (and so on) factors that influence the way we see things and behave.

But to assume a new insight into our views would then lead us all to apply corrective action seems to underestimate the complex web that drives our behaviour individually and collectively. Put simply, it overestimates our ability to overcome years of conditioning and habit.

Much of the research into the remedial programmes which aim to bring ‘unconscious biases’ into consciousness and deliver strategies to counteract the effects reveals the limitations.

Such programmes work for roughly a third of participants – and often for a short-lived period only. The programme will have little to no effect for another third and for the final third the programme may succeed in further entrenching their views.

WHAT WE DO KNOW...

REVEALED: BRITAIN'S MOST POWERFUL ELITE IS 97% WHITE

We know that unconscious bias exists. We know it’s prevalent throughout our social and institutional structures. And we know there’s no clear consensus around what it is.

We also believe the notion of unconscious bias holds a certain appeal. It plays into ideas of intriguing mental processes about which individuals have little awareness, and which require the expertise of psychologically-informed scientists or therapists to reveal.

But this both excuses and robs the individual of agency. How can we hold to account that which we are unaware of? If bias was unintended, where’s the crime?

We know, too, that some approaches to conceptualising and understanding the subject are more coherent and compellingly evidenced than others. They provide convincing answers to the key questions: how does bias arise; and how can we ‘cure’ it?

To follow is a survey of the strongest evidence answering these questions.

...HOW BIAS ARISES

A long tradition and evidence base from cognitive psychology illustrates how implicit responses, or biases can arise, much of which has been summarised by psychologist Daniel Kahneman. His work, in collaboration with a number of other respected researchers, and in particular Amos Tversky, provides evidence on how rapid associations and creating mental shortcuts help us understand the world around and allow us to operate effectively.

It works like this: Many of our cognitive processes are automatic.

So that we can function effectively, our brains have evolved various shortcuts to enable us to make sense of complex information quickly. For example, when we see an image of a human face with a specific expression, we can quickly identify the emotion. We can then automatically – and without consciously intending to – associate all kinds of additional information, such as what the person might say or do next.

These thought (cognitive) processes and mechanisms greatly help us process complex information and to generalise from one situation to another to understand it.

However, these very same internalised and automatic mechanisms facilitate stereotyping, over-generalising and other faulty or incomplete judgements. It is these mechanisms that can lead us into biased-thinking outcomes - both positive and negative.

Such unconscious bias can also arise through cognitive deceptions. These occur in a number of learned ways as the evidence shows.

The two main channels of cognitive activity were characterised by Kahneman, as ‘System 1’ and ‘System 2’ thinking.

Box 4

‘System 1’: This type of cognitive activity encompasses the many shortcut cognitive operations that are automatic. It includes mental processes such as perceiving depth and distance, detecting emotions (and often their accompanying physical sensation), orienting to the source of a sudden sound and so on. Many of these originate in early childhood and others become automated through sustained exposure and/or practice.

This ‘system 1’ thinking is also an automatic process in the way our associations are made quickly and unintentionally, thereby allowing our brains to construct an impression or form a belief that helps us structure the diversity of information we continuously receive (the Muller-Lyer illusion, Box 4, is an example of this).

THE RISKS OF AUTOMATIC THINKING

The ‘system 1’ cognitive processes are fantastically helpful in certain conditions; helping us to respond quickly to all kinds of stimuli by minimising doubt and ambiguity and giving us a clear path to follow - have a look at Box 5

However, like with most short-cuts, there are inherent risks, here in the form of unexamined inferences, invented causes and intentions, selective attention, confirmatory biases, the misinformation effect (seen most alarmingly in eye-witness accounts of dramatic incidents or crimes) and biased evaluation of data.

Such mental shortcuts leave us with impressions, feelings and inclinations, which, when ‘endorsed’ by ‘system 2’, start to become embedded as intentions, beliefs and attitudes. These start to coalesce into coherent patterns of activated ideas in our associative memory – heuristics or mental shortcuts.

Box 5 - Effortful attention distracts

Effortful attention to a specific task can make us effectively blind to other stimuli.

This was amusingly demonstrated in a famous experiment (Simons and Chabris, 1999) in which participants were asked to watch a film of two teams passing a basketball and count the number of passes made by the white team. They were asked to ignore the players dressed in black.

During the film, a person dressed in a gorilla suit crosses the field of play, chest-thumping along the way for a period of nine seconds.

Across a very large sample of participants (many thousands) in the experiment, about half did not notice anything unusual, and were extremely surprised when told of the sequence.

The counting task, plus the instruction to ignore one of the teams has required all their attention, to the exclusion of a substantial potential stimulus.

Examples abound.

If as young children we repeatedly see hoodie-wearing Afro-Caribbean men associated with crime (rightly or wrongly) in the media, we develop a set of automatic associations and responses. Various studies show that if we then see a young black man running past us down a street being chased by an older white man yelling at him to stop, our pre-programmed beliefs lead us to conclude the younger man has committed some crime, not that the older man is threatening the other.

If we are constantly told that women are more ‘nurturing’ than men, we develop the automated association and then apply that in deciding suitability for certain jobs.

If we have repeatedly been exposed to the idea that middle-aged white men occupy positions of power in institutions, then we develop an automated judgment process that will reinforce that stereotype which may result in faulty decision-making.

The list goes on… This is the stuff of unconscious bias.

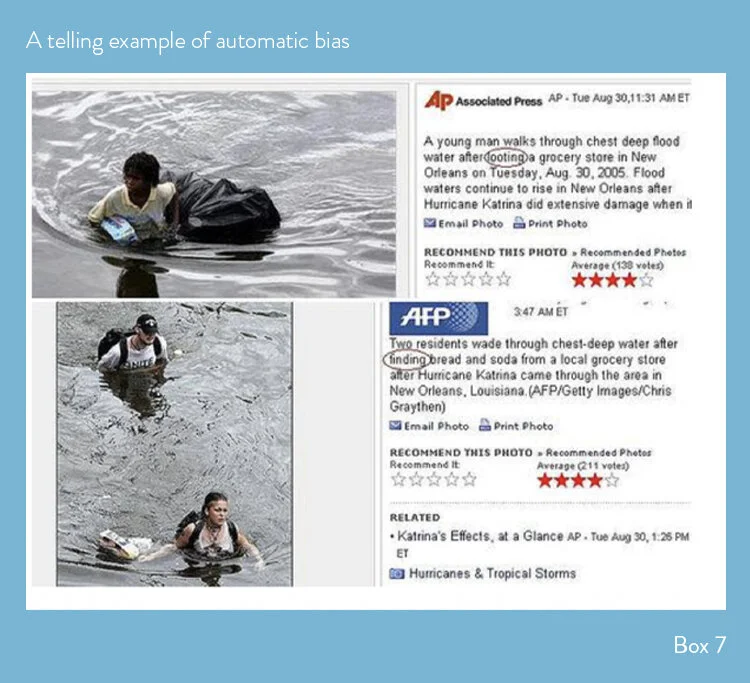

LET’S BE MORE EMPOWERED AND ACCURATE; LET’S CALL IT AUTOMATIC BIAS

Through an understanding of how our automated and effortful cognitive processes work separately and together, and how we come to ‘learn’, we can understand how biases arise.

Put simply, if we are given repeated exposure to certain stimuli we develop automated, unintentional but potentially faulty judgments.

There is perhaps less mystery and intrigue here than the term unconscious bias implies…and for this reason we prefer the term automatic bias. Automatic in the sense that patterns have formed with minimal deliberate thinking, and through practice, have become habituated. In times of high pressure we revert to them automatically.

WHAT ELSE DO (AND COULD) WE KNOW FROM NEUROSCIENCE

New developments in brain imaging technology, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, fMRI, allow neuroscientists to see what areas of the brain become active in real time when people are engaged in various kinds of activities and tasks.

This has shed new light on what might be going on in our brains at a neural level when we make automatic associations that are outside our conscious awareness.

In a ground-breaking experiment, cognitive neuroscientist Elizabeth Phelps and colleagues looked at the levels of activation in the amygdala region of the brain when white individuals were shown white and black faces in an IAT task.

The amygdala is known to be involved in emotional learning, memory and plays a key role in social evaluation. It is a primitive part of the brain that responds quickly and automatically to stimuli, without the engagement of conscious thinking. Research suggests it has a key role in unconscious processing of social signals, but not in the conscious formation of attitudes – something that could explain dissociation between the two.

The experiment found greater levels of activation in the amygdala region of the brain in the white participants when viewing unfamiliar black faces, compared to when viewing white faces. Individuals also took an IAT on race – the higher the IAT score (unconscious association) - the greater the amygdala activation.

What is even more interesting is that when the experiment was repeated using well-respected and famous black faces, instead of unknown black faces, the pattern of increased amygdala activity with increased IAT score disappeared.

A white over black preference was still seen in the IAT when famous black faces were substituted, but to a lesser extent than with unfamiliar faces. This suggests that familiarity plays a role, but it does not fully explain the results.

Phelps and colleagues suggest that differences in responses can be explained by culturally acquired knowledge about social groups which is moderated by our individual knowledge and experience – as in the case of the famous black individuals.

Advances in neuroscience provide the real possibility of understanding how our social biases may be rooted in the brain’s mechanisms. We know the brain is malleable and that new neural pathways can be added with learning and experience.

So, could a better understanding of these mechanisms be one route to better understand and learn to manage our biases?

WHAT WE DO KNOW...

...HOW TO CURE IT

Given our understanding of what unconscious bias is – a process of automated thinking that results from various processes that help our brains make shortcuts – and how it develops, we ought to be able to reverse engineer the process. And this seems to be a promising approach.

Our development of automated racial bias, for example, arises from exposure to repeated associations such as between black men and crime. Applying forms of the same kinds of learning we’ve seen above, but in reverse, give us ways to potentially counteract the effects of unconscious bias: repeated exposure to positive exemplars of black men in non-crime-related situations; repeated pairings of stereotypes disconfirming data; or reducing the perception of difference between white men and black men.

All these methods have impressive scientific names deriving from learning theory – such as ‘counter-stereotype conditioning’ or ‘aversive conditioning’ - and involve various types of priming - see box 6 for an example. But they share the fundamental premise that the bias has been learned and automated (internalised to the point of unawareness) and can then be unlearned or re-learned differently using similar processes. Giving people time to slow down to examine their thought processes is a necessary precursor to successful reverse-engineering.

At a different level of analysis, the idea is that we all belong to one group or another, black people-white people, women-men, and that our unfamiliarity with members of the ‘other’ group is part of the reason we have built up the stereotypes in our brains.

Increasing familiarity with the ‘other’ group should therefore reduce the need to revert to stereotype usage, or teach us that we are each more than one characteristic. Depending on the criteria chosen, we can have much more in common than not.

Interestingly, the research shows clearly it is the quantity of contact (not necessarily quality of contact) that reduces automatic bias.

Box 6 - Ridley Stroop’s classic visual priming study shows the power of priming in reverse…

It takes longer to read the words on the first line because they are incongruent with the colours. The words on the second line have no relationship with colours, making it easier to read them out.

What we don’t fully know yet is how much or how long such reverse engineering takes to materially reduce or eradicate previous learning. However, given that we do know that most training attempts so far evaluated do not lead to sustained bias reduction results, we can safely predict that a one-, two, or three-day training programme is unlikely to have the desired effect.

Apart from training, we do know something about the kind of circumstances in which automated thinking and therefore potential bias creeps in. When we have to make decisions or judgement at speed or under pressure, automatic thinking (and bias) takes over. When we are tired or hungry automatic thinking (and bias) creeps in.

It is unsurprising therefore that examples of automatic bias in action seem to occur most often in high pressure or ‘emergency’ situations – just when more deliberative effort is required.

There are clearly some easy fixes that can be built into systems to mitigate against automated thinking (and bias):

doctors (junior or otherwise) should not be working 36 hour shifts without proper breaks for physical and cognitive rest and food;

lawyers or judges should not be asked to make important decisions (probation, bail, sentencing) for hours on end without adequate cognitive rest and food:

recruiters should be restricted from making hiring decisions at the end of long days of assessing.

You get the picture.

THE REALITY WE NEED TO FACE UP TO IS...

...THAT SHEEP DIP TRAINING IS VERY UNLIKELY TO WORK.

The main rationale for such training, especially in the absence of any proper evaluation, is to be seen taking action. What does this say about us? That we want to take the easy route? That we are not prepared to put the time and effort into developing a real understanding and some better approaches? That positive PR is more important than real action?

...THAT GLORIFYING ONE MEASUREMENT INSTRUMENT IS NOT GOING TO SOLVE THE PROBLEM.

Many love the IAT. At first glance it looks like it will give us some quick wins and it appears to provide a relatively simple and intuitively appealing explanation and potential for addressing the problem. However, the IAT is not a solution to the problem. It is an illustration of it, and feeds off liberal guilt and the promise of speedy solutions. Back to the utopian notion that insight sets us free, research with the IAT has definitely proved otherwise.

...THAT AUTOMATED BIASES ARE NOW EMBEDDED IN SOME OF OUR MOST IMPORTANT INSTITUTIONS, EVEN THOUGH WE HAVE SOME UNDERSTANDING OF HOW THIS HAPPENED.

At some level we all appreciate that bias is a difficult problem and will take time to address. Perhaps we have parked it. We’ve put it in the ‘too difficult’ box. Maybe we’re simply fatigued. Training of various sorts will help, but it will take a sustained effort, not just a one- or two-day programme. What kind of discourse do we need to move us forward to the next level? How are our very positions of power and privilege getting in the way of us making meaningful progress? We need a more sophisticated approach, acknowledging our own lenses and the complex web of stories and ideas shaping who and how we are. Our institutions are as they are because we are as we are, and vice versa. The stalemate is only broken by us doing things differently.

...THAT AUTOMATED BIAS IS RIDING ON THE BACK OF CAPITALISM AND CONSERVATISM.

The conservative ethos consolidates bias by contesting ways to get real inclusivity onto the agenda. Not only that, capitalism backs it up by insisting we quantify all our efforts and outcomes in relation to embedding diversity, equality and inclusivity in short-term financial metrics. The old adage of every homophobic man only behaves as such because he fears being treated as he treats women is potentially no less true of our approach to race, religion, class.

...THAT UNCONSCIOUS BIAS IS BEING USED AS AN EXPLANATION/EXCUSE FOR BIASED OUTCOMES.

Expressions of overt prejudice are increasingly socially unacceptable and are seen to be on the decline, but the negative outcomes of bias are not. Because of this, unconscious bias is now the more acceptable face of racism, sexism, ageism, and so on. This may be a good thing; automatic bias is a helpful frame of reference through which to understand how negative or unequal or prejudicial outcomes arise. However, it is not an excuse or a means of exoneration.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

WELCOME DISCOMFORT

It’s been said that the British reluctance to learn foreign languages is in part a fear of looking stupid. Children who learn languages at an early age throw themselves into linguistic experimentation, and with it, a willingness to play around with new sounds and a sense of playfulness with getting it wrong. Awkwardness, embarrassment, getting it wrong, looking foolish seem to tap into some national anxieties.

And yet, if we’re not willing to be clumsy and throw ourselves into conversations with folk from different backgrounds and perspectives, how will we ever move forward?

We can’t wait magically for the time to arrive when our understanding suddenly coalesces into a moment of personal epiphany. It takes direct action. It takes us all being willing to get into conversation with one another, trusting that in curiosity there is no wrong.

DEMAND MORE

We strongly advocate that commissioners of bias ‘training’ dramatically lift the bar in the expectations they set for their providers to evidence the impact and cost effectiveness of their interventions.

Ask your providers: What evidence do they have in terms of reaching lasting attitudinal and behavioural change?

There is clear evidence that for most participants no good will come of PR-driven, sheep-dip approaches. As we’ve seen, for some ‘trainees’, prejudicial beliefs will become more deeply embedded and manifest in harder to catch micro-aggressive acts.

Ask your providers: What evidence do they have of doing no harm? It’s not an unreasonable question given what we know might happen for some participants.

We recognise that there’s an ‘emperor’s new clothes’ appeal to the IAT and its related interventions and we recognise that we collectively need to find alternatives that are equally engaging and leave folk sitting up and feeling held to account.

This is as true of bias work as it is of corporate on-boarding, culture change, sales strategies efforts, and so on. Instructions, rules and sanctions can only do so much. Dialogue can do the remainder.

BE THE CHANGE

Ask yourself: How do the ideas I have about my partner and their role in my life shape how I’m approaching the business topic I’m grappling with? How does my gender influence how I am writing this policy document? How does my (invisible) disability shape how I approach my leadership role?

The intersection of the many narratives influencing how we are in the world inevitably influences what we see and how we interact with the world. How could it not? We each need to be more curious in seeking to understand our own personal story

We need to do a better job truly understanding the implications of this infusion of stories within ourselves, just as we need to do a better job of understanding our collective behaviour and how these facets feed into issues of blindness to issues of power and privilege.

Our individual behaviours aggregate into attitudes and behaviours which cut deep into contemporary life. Looking within is and must be a key starting point if we can hope for any lasting and material change.

Here is a small selection of relevant reading should you wish to read more...

“Fitzgerald, C., Martin, A., Berner, D. & Hurst, S. (2019). Interventions designed to reduce implicit prejudices and implicit stereotypes in real-world contexts: a systematic review. BMC Psychology, 7:29

Forscher, P.S., Mitamura, C., Dix, E.L., Cox, W.T.L. & Devine, P.G. (2017). Breaking the prejudice habit: Mechanisms, timecourse, and longevity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 72, 133-146.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1464–1480

Kahneman, D. (2012). Thinking fast and slow. UK: Penguin.

Phelps, E.A., O’Connor, K.J., Cunningham, W.A., Funayama, E.S., Gatenby, J.C., Gore, J.C., & Banaji, M.R. (2000). Performance on indirect measures of race evaluation predicts amygdala activation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 12(5): 729-738.

Simons, D.J. & Chabris, C.F. (1999). Gorillas in our midst: sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Perception, 28, 1059-1074.”